Within YCombinator’s Request for Startups 2025, we can see that YC is requesting companies that are essentially operating as service companies (agencies) in the front, with AI as the backend. or what they like to call them, "full-stack AI companies".

Companies not selling tools to law firms, but becoming AI-powered law firms.

Not selling software to consulting companies, but replacing McKinsey.

At least 9 startups in the Winter batch are just that, across insurance, consulting, HR, accounting, mortgage, and healthcare - all betting they could own both the technology and the service delivery.

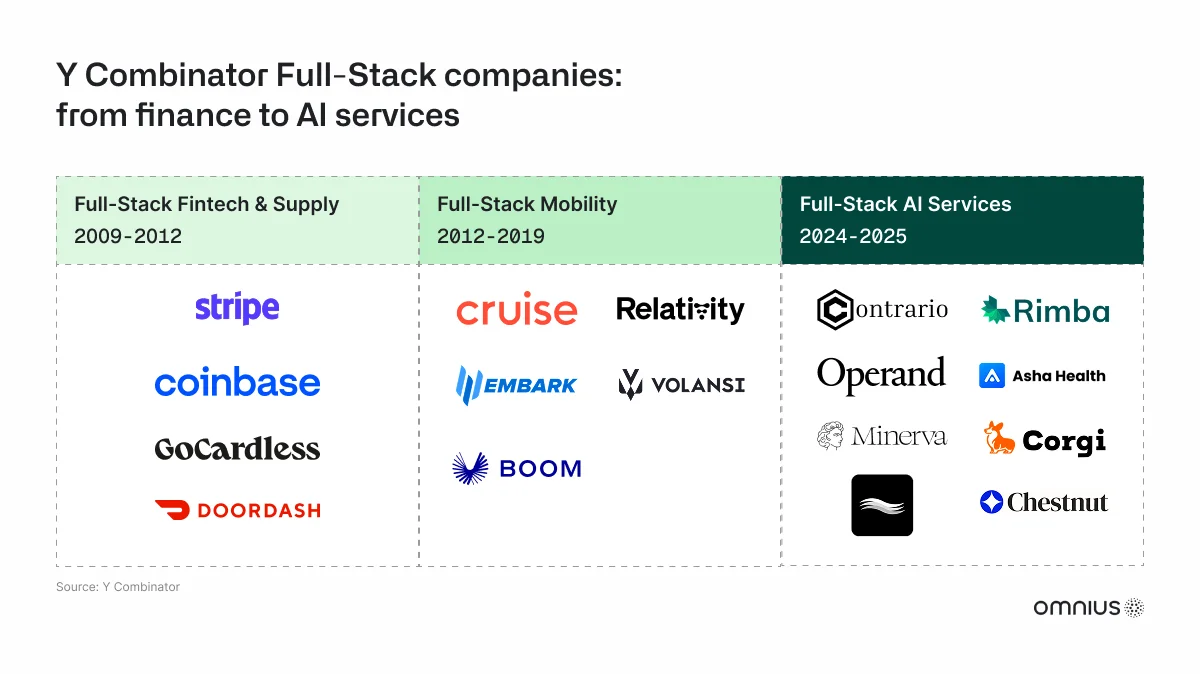

This represented a complete inversion of YC's traditional playbook.

In the 15 years, YC had backed only about a dozen service-focused ventures, with software products massively dominating their portfolio in this timeframe. The 2024 year brought a change - a single batch produced nearly as many full-stack AI companies as the entire prior decade and a half.

For two decades, the software industry learned that horizontal tools beat vertical services.

Salesforce beat consulting firms.

Shopify beat building stores.

The tool always wins because it scales without adding headcount, but AI might be very likely to change this equation. When the vertical AI market projects growth from $10 billion to $115 billion by 2034, and analysts predict it could be 10x larger than traditional SaaS, something fundamental is changing about where value is to be found.

The tool-versus-service divide

For two decades, the software industry operated on a simple principle: tools beat services; the economics made this inevitable.

Salesforce didn't compete with management consultants by offering better consulting - they built software that made sales teams more productive, then sold it to thousands of companies simultaneously, with the marginal cost approaching 0.

Revenue grew without proportional headcount - gross margins hit 70% to 80% as the same software served customers 1,000 the same way it served customer one.

Traditional professional services couldn't match that model. McKinsey, Deloitte, and BCG sold expertise and labor, where revenue scaled linearly with headcount. A consulting project for one client required dedicated consultants, where the process of serving more clients directly meant hiring more consultants.

The professional services market reached $6.37 trillion globally by 2025, but margins stayed compressed between 20% and 30% because scaling meant adding people.

The value proposition was different as well.

SaaS tools were betting on efficiency gains. If software made a sales representative 10% more productive, the company might pay 1% to 5% of that employee's salary for the tool. Aggregate software spend per employee rarely exceeded 10% of their cost. Pre-2022, the software enabled work, but humans still did the work.

This created the conventional knowledge that dominated venture capital for a generation. Horizontal platforms that could serve multiple industries always beat vertical solutions tied to specific sectors. Tools that scaled infinitely always beat services that scaled linearly.

Software always beat consulting.

This logic rested on an assumption that the implementation would always be cheap enough that companies could do it themselves once they bought the tool.

The tool vendor shipped software, the customer implemented it, and everyone captured their portion of value, with the market barrier being building the software, not deploying it.

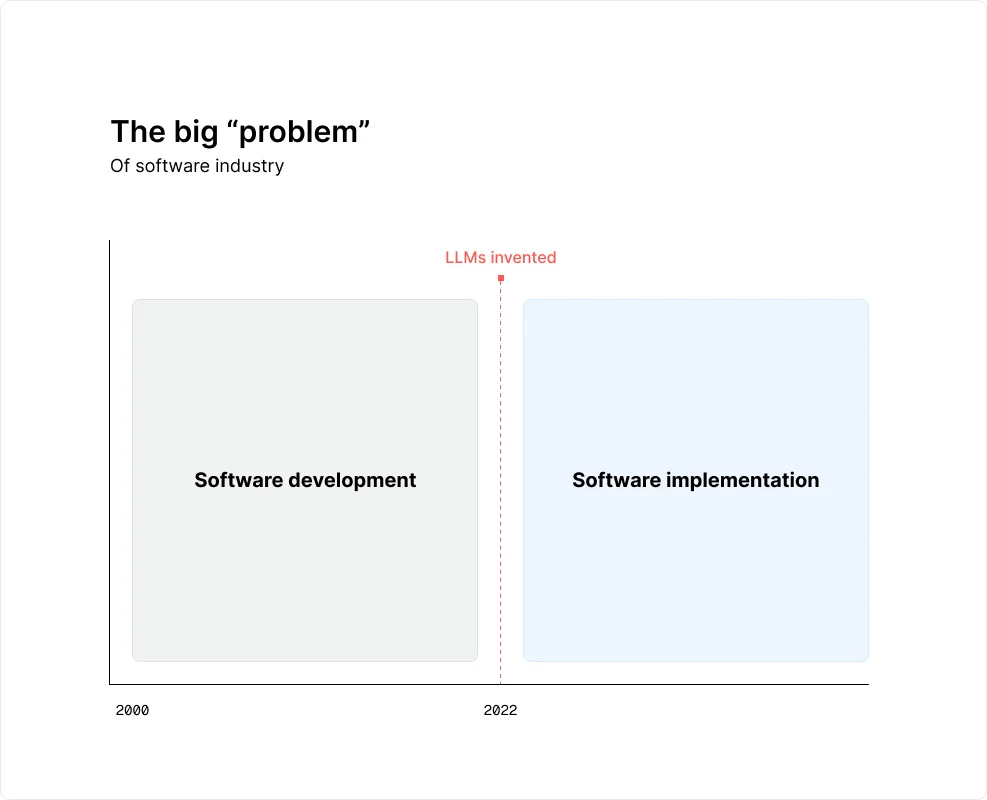

AI is directly breaking that assumption in both directions. Building software became dramatically cheaper, but getting software to actually deliver value became dramatically harder.

AI makes building cheap, implementation expensive

Between 2022 and 2025, the global developer population grew from 31 million to 47 million - a 50% increase in three years. Although this number might look optimistic, it only counts people who identify as developers (now, a pretty wide group), making it a false positive.

Within this timeframe, GitHub Copilot made developers 55.8% faster in controlled experiments, with the time to merge code dropping by half.

Developers reported being in flow state 39% more often. Tools like Cursor, Zencoder, Windsurf, and Replit turned non-technical people into builders.

For example, Replit grew from $2.8 million in revenue to over $150 million annualized by late 2025, with projections hitting $1 billion by 2026. Their pitch was "vibe coding" - you don't need to know how to code, you just need to know what you want.

The supply of people who could build software exploded, and the cost of building software collapsed.

This created exactly what economic theory predicts when supply increases intensively: commoditization.

In November 2024, Codeium launched Windsurf as the "first agentic IDE," promising developers could delegate entire features to AI. Within months, competitors had identical capabilities. By April 2025, Windsurf dropped its price from $35 to $30 per user to match Cursor's pricing. The features that seemed revolutionary in November became table stakes by spring.

Cursor raised $60 million from a16z at an $400 million valuation.

Augment raised $252 million.

Poolside raised $126 million in Seed Round.

Yet despite massive capital, differentiation was still missing.

Every tool offered autocomplete, chat, multi-file editing, and agentic task completion - which gets us exactly to the whole point - the value wasn't in the features anymore, it was in which one integrated best with your existing workflow, which one your team already used, which one felt slightly less annoying, and which one had access to closed, proprietary data.

Development became cheap.

But getting what you built to actually work became expensive.

Cledara's 2025 report of enterprise software buyers found that 82% of organizations are experimenting with AI tools, but only 46% report seeing tangible value from those experiments. The gap between "we bought it" and "it works for us" widened as capabilities expanded - a clear example of negative correlation.

We can conclude that organizations aren't struggling with access to AI; they're drowning in it.

Studies revealed that enterprises use only 47% of their SaaS licenses, wasting an average of $21 million annually on software they own but can't effectively deploy.

The average company manages between 106 and 112 SaaS applications, and processes 247 renewals per year - one renewal every single business day, clearly indicating they have been adding software faster than they could implement it.

The bottleneck has now changed.

Building software used to be hard and expensive; now it's easy and cheap.

Implementation used to be manageable; now it's the entire challenge.

You can build an internal tool in hours, but getting your organization to actually use it effectively - that takes months or years, if it happens at all. This inverts the traditional economics.

When building was expensive, companies needed tools to make building cheaper.

When implementation is expensive, companies need something else entirely.

They need someone to own the entire process, from technology to deployment to ongoing value extraction & delivery.

This is not an isolated suboptimality; the same pattern is repeated across different industries. AI could generate the code, write the copy, create the images, and draft the documents.

It couldn't decide what should be built, for whom, or why; it couldn't navigate organizational politics, regulatory requirements, or customer relationships. It couldn't own the context and outcome.

This created an opportunity for a different model. Not tools that make companies more efficient at implementation, but services that own implementation entirely, using AI to make service delivery economically viable at software margins. (What brought us to full-stack AI companies)

Full-stack AI model emerges

Y Combinator's Winter 2024 had at least 9 startups positioned as full-stack AI companies, built entirely on AI infrastructure, competing directly with incumbents by owning both the technology and the service delivery.

The contrast with YC's past batches was more than obvious - in 15 years and over 5,000 companies, YC had backed only about a dozen true full-stack ventures - primarily fintech startups in the early 2010s like Stripe and Square, followed by autonomous vehicle companies between 2012 and 2019.

Software-first companies dominated everything else, until 2024.

A single batch on that year produced nearly as many full-stack AI companies as the entire prior decade and a half.

The pattern across these companies shares three consistent characteristics.

1. First, they operate in industries with high labor costs and repetitive manual processes - exactly where AI can deliver the most value.

2. Second, they combine AI engineering capabilities with deep domain expertise, often hiring from the industries they're disrupting.

3. Third, they compete on outcomes rather than efficiency, charging for results delivered rather than software licenses sold.

YC historically avoided capital-intensive, operationally complex businesses for a good reason. Full-stack companies require more capital, face regulatory hurdles, and scale differently than pure software.

YC backed them anyway because the “problem” changed, and unit economics changed. When AI makes service delivery viable at software margins, the trade-offs that once made full-stack models unattractive become acceptable.

Operand: "An AI to Kill McKinsey"

Operand exemplified the model. The company positioned itself with a tagline that left no ambiguity: "An AI to Kill McKinsey." They aren't selling software to consulting firms, but building a consulting firm powered by AI, starting with pricing and discount strategy for e-commerce and retail brands.

The team combined exactly what this model requires: AI engineering expertise plus consulting domain knowledge. They built an AI that analyzes a brand's entire data ecosystem - sales, inventory, competitor pricing, ad spend, customer behavior, and delivers pricing recommendations in real time.

The company raised $3.1 million in seed funding from Felicis, Y Combinator, SV Angel, and Soma Capital in May 2025.

What makes Operand significant isn't the technology alone, but rather a business model, as they own the outcome.

Unlike consulting firms, Operand doesn’t only give recommendations. The client doesn't implement Operand's suggestions - Operand's AI implements them directly, which it the key difference between "here's what you should do" and "here's what we did for you" represents the gap between tool and service, between enabling and executing.

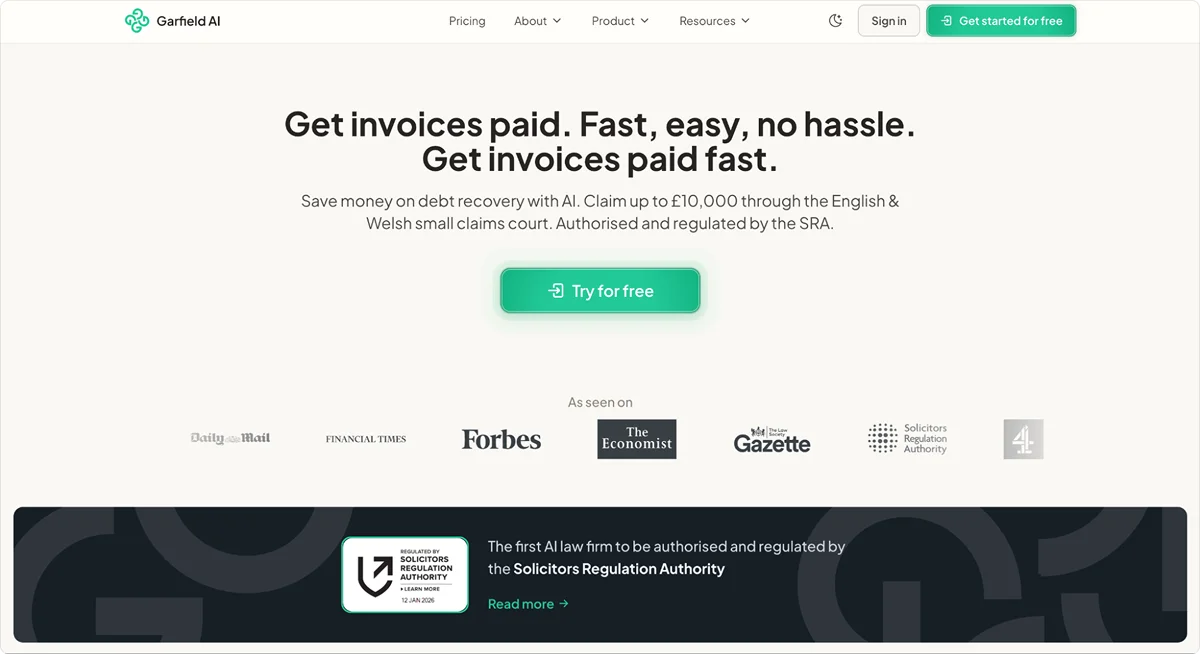

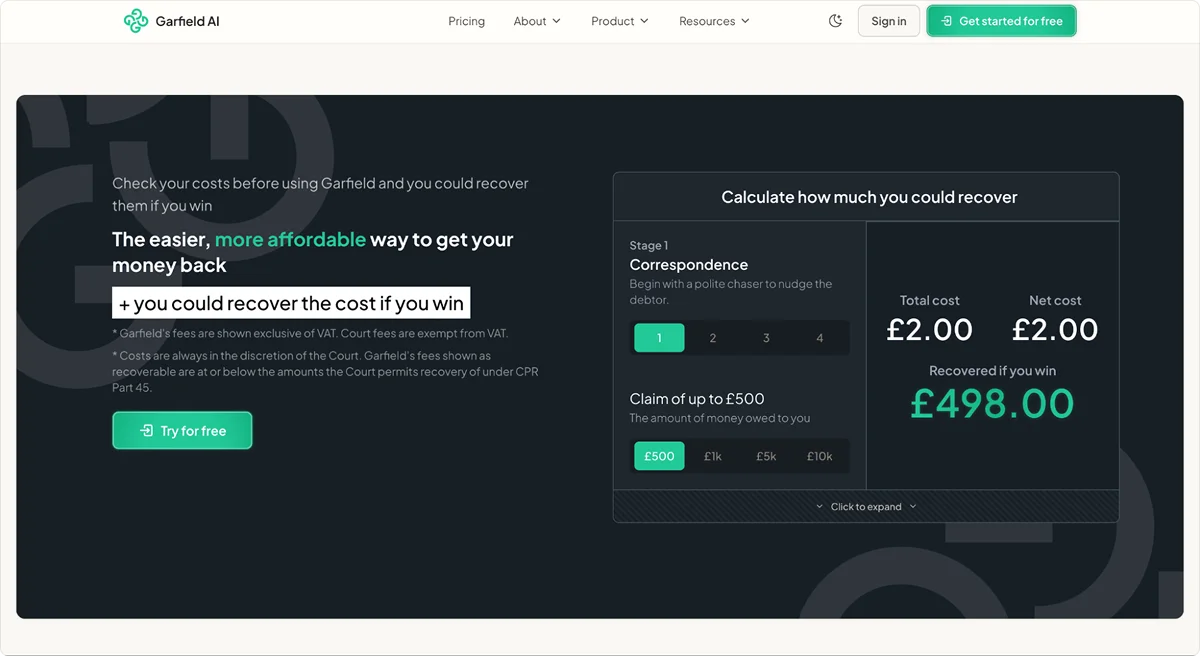

Garfield AI: First regulated AI law firm

Regulatory approval represents another critical validation of the full-stack model.

Professional services industries have licensing requirements specifically designed to prevent unauthorized practice. Legal services, healthcare, and accounting - these sectors maintain strict regulatory oversight.

Proving that AI-powered companies can meet these standards, while still offering dramatically different economics than incumbents matters beyond any single company, it’s a concrete value addition industry-wide.

Garfield AI demonstrated this in May 2025, becoming the first AI law firm approved by the UK's Solicitors Regulation Authority. According to the SRA, they don't sell legal software to law firms - they are a law firm, powered by AI, competing directly with traditional firms on price and service.

The economics speak directly to the implementation gap. Traditional legal services for debt collection cost hundreds or thousands of pounds.

Garfield charges £2 for a debt recovery letter and £50 for a small claims court filing. This isn't a marginal pricing improvement, but an order-of-magnitude cost reduction enabled by AI handling the execution while human lawyers provide oversight and approval.

The addressable market is substantial, with UK SMEs holding between £6 billion and £20 billion in uncollected debts annually. Traditional law firms can't economically serve this market at scale.

The fees required to cover lawyer time make small debt collection unprofitable, and Garfield's AI changes the unit economics entirely - they can profitably serve cases that traditional firms ignore.

The team is tiny - just five employees, including a City lawyer and a quantum physicist as co-founders. A dozen law firms use Garfield's platform on a white-label basis. They have proved that the full-stack model is working: own the technology, own the regulatory compliance, own the service delivery, and serve customers at price points incumbents can't match.

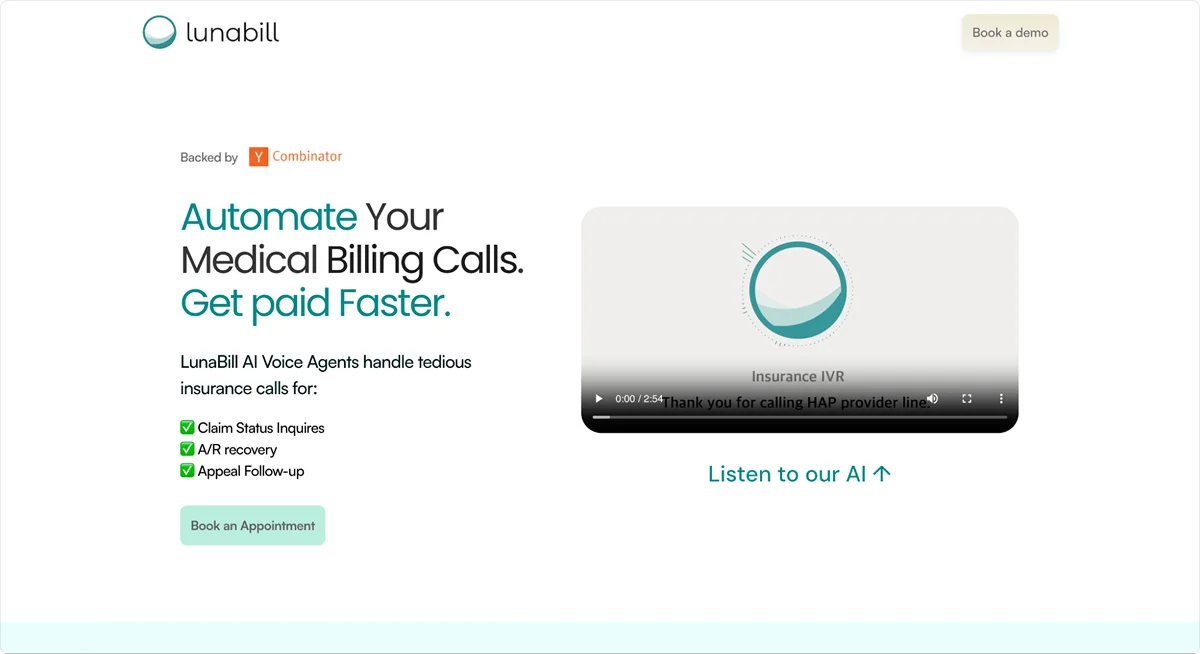

LunaBill: Healthcare billing automation

Billing represents one of the most labor-intensive back-office functions in medicine, with teams spending 80% of their time on repetitive insurance claim follow-up calls.

It's necessary work that doesn't require clinical judgment - exactly the profile where AI service delivery can replace human labor entirely while maintaining quality.

LunaBill built AI voice agents that automate these calls end-to-end. The company launched in July 2025 and reached $764,000 in contracted annual recurring revenue by year-end, with $428,000 already live and the remainder launching by January 2026.

Customers report a 10x increase in claims followed up per biller in the first week. The company converted 100% of pilots to paying customers and automated over 50,000 calls.

This company isn't selling software that helps billing teams make more calls, but replacing the calling function entirely. The billing team focuses on exceptions, complex cases, and strategic work, while the AI handles the repetitive execution. This is service delivery, not software licensing, and vvalue captured reflects that difference.

The velocity at which these companies are scaling validates that the model has gone from experimental to proven.

They're generating revenue, signing sophisticated enterprise customers, and demonstrating unit economics that work - and the market is increasingly rewarding these types of companies - that own the technology & implementional layers of work.

Why full-stack economics work now

Traditional SaaS captured efficiency gains of employees, vertical AI captures work itself, and this is the most important difference that is visible directly in the pricing power and margin structure.

Traditional SaaS companies priced based on seats or usage. For example, Salesforce might cost 1% to 5% of an employee's salary, the software made the employee more productive, but the employee still did the work. SaaS typically captured 1% to 5% of an employee's value.

Aggregate software spend per employee rarely exceeded 10% of their cost.

Vertical AI companies price differently because they deliver value differently, not through efficiency - but the replacement.

Vertical AI vendors are capturing 25% to 50% of an employee's value - five to ten times what traditional SaaS could command.

This isn't theoretical pricing - it's what customers are actually (reportedly) paying. When AI handles work that previously required a $100,000 employee, charging $25,000 to $50,000 for the same output is still a massive cost reduction for the customer while representing much higher revenue per customer for the vendor.

The addressable market expands proportionally.

Traditional SaaS targeted the $450 billion enterprise software market - roughly 1% of US GDP.

Vertical AI targets the $11 trillion US labor market - specifically the knowledge work that AI can now automate, with business and professional services representing 13% of US GDP, dominated by repetitive language-based tasks that were previously out of bounds for software.

This explains why Bessemer Venture Partners predicts that "Vertical AI's market capitalization will be at least 10x the size of legacy Vertical SaaS."

The markets being addressed are fundamentally larger. Software spend is capped by efficiency budgets; the labor spend is capped by what work needs to get done.

The margin structure validates this, with early vertical AI companies maintaining 65% to 80% gross margins - comparable to traditional SaaS, while growing at 400% year-over-year compared to 95% for horizontal AI platforms.

Vertical AI companies achieved median ARR growth of 180% versus 95% for horizontal platforms.

These margins work because AI fundamentally changes the cost structure of service delivery.

A traditional law firm scales linearly - more clients require more lawyers, while Garfield scales like software - the AI infrastructure serves the 1,000th client the same way it serves the first, with marginal cost approaching zero.

The business model looks like services (own the outcome, charge for results), but the economics look like software (high margins, exponential scaling).

The same pattern appears in pricing models.

Traditional consulting bills by the hour or project. Vertical AI companies can bill on outcomes, subscriptions, or usage - whatever captures the most value. This is also know as Result as a Service (RaaS) model.

This is why full-stack companies can compete with both incumbents (legacy service providers) and horizontal tools (software products) simultaneously.

Against traditional services, they offer dramatically lower costs enabled by AI, while against horizontal tools - they offer implementation and outcomes rather than just software.

FSAC occupy the space between "expensive but comprehensive" and "cheap but requires you to implement it yourself."

On the downside, the capital requirements are higher than pure SaaS. Full-stack companies need to build AI infrastructure, handle regulatory compliance, manage service delivery operations, and maintain quality control.

But when the unit economics support capturing 25% to 50% of employee value instead of 1% to 5%, the additional capital is justified by the revenue potential.

Although, the article so far suggests that FSAC is the closest thing to the perfect business model, the important thing to highlight is that the timing is a factor of a great essence. Just 5 years ago, things looked very different.

This market readiness is what changed between Atrium's ($75M legaltech startup) failure in 2020 and the current wave of full-stack AI companies.

- The technology matured enough that service delivery could actually work at software margins.

- The implementation gap widened enough that owning implementation became more valuable than selling tools.

Combination of the two created a window where the full-stack model finally makes economic sense.

The willingness to pay follows from this economic structure.

Enterprises traditionally require 5x to 10x ROI from software investments. But according to Gartner's 2024 CIO survey, they're accepting 2x to 3x ROI for AI initiatives because the value delivered is fundamentally different.

When AI replaces a $100,000 employee entirely, a 2x ROI means charging $50,000 - which is still a 50% cost reduction for the customer while representing ten times what traditional SaaS could capture from that same employee.

This is why investors are betting on vertical AI despite the operational complexity. The market size is larger, the value capture is higher, the margins are sustainable, and the growth rates exceed what horizontal tools can achieve.

The full-stack model works now because companies became aware of the next big problem being AI implementation, technology has advanced, and the economics finally support it.

Vertical AI acceleration

The vertical AI market was valued at $10.2 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $115.4 billion by 2034 - a 21.6% annual growth rate. Alternative projections are even more aggressive: from $5.1 billion in 2024 to potentially $100 billion or more by 2032.

Corporate adoption accelerated dramatically, as well.

McKinsey's 2025 research found that 78% of organizations now use AI in at least one business function - up from 55% in 2023. More significantly, 16% are running fully AI-led operations, up from 9% the prior year. This isn't experimentation anymore, it's deployment at scale.

Over $200 billion was invested in AI in 2024 alone - seven times the Manhattan Project's inflation-adjusted cost. Within that, vertical AI has started to capture an increasing share as investors recognize that industry-specific applications are where sustainable businesses get built.

Studies confirmed this isn't isolated to a few companies - early vertical AI firms are reaching 80% of the average contract value of traditional vertical SaaS products - despite being significantly younger, with growth rates of 400% year-over-year common in the cohort.

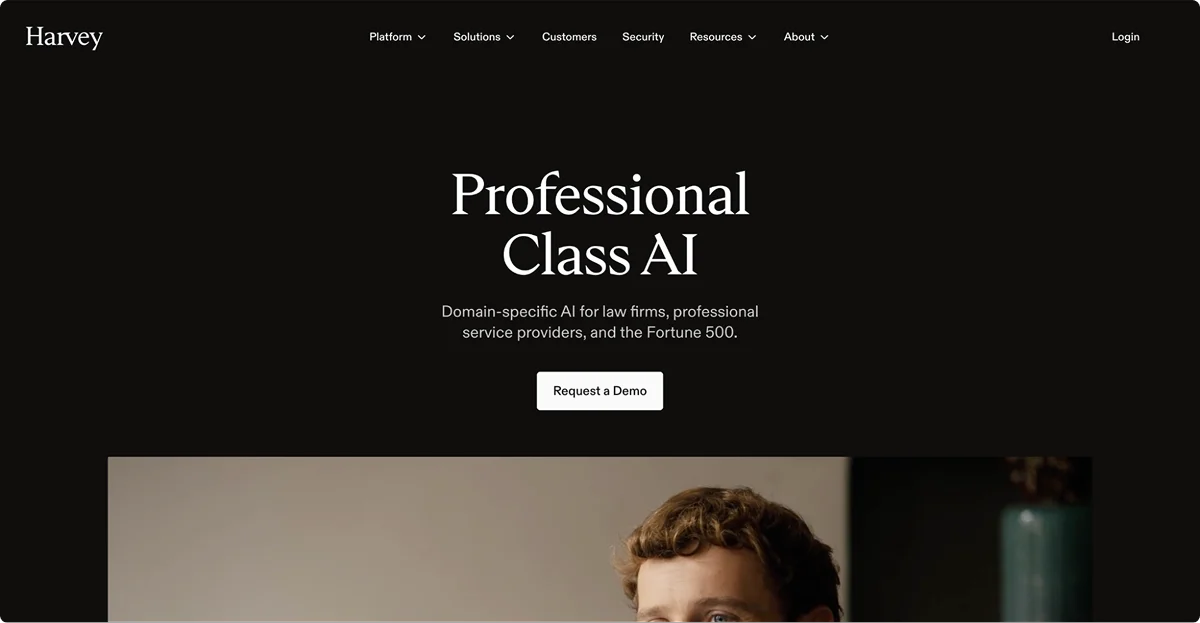

Harvey AI: Vertical acceleration in practice

The legal AI platform started 2025 at a $3 billion valuation in February.

By June, they'd reached $5 billion.

By December, $8 billion – nearly tripling in a single year.

Revenue grew proportionally: from approximately $50 million in ARR in February to $100 million by August and an estimated $150 million by November.

Harvey served roughly 40 law firms in 2024.

By February 2025, they had 235 customers.

By August, over 500 - including 50 of the AmLaw 100 firms, the largest and most sophisticated legal practices in America.

Major enterprises followed: Comcast, KKR, and PwC all became customers. Weekly active users grew 4x year-over-year.

Harvey's pricing strategy mirrored the value they captured: approximately $1,200 per lawyer per month with roughly 20-seat minimums. A mid-sized law firm with 50 lawyers pays $720,000 annually.

That's substantially more than traditional legal software, but still a fraction of what hiring additional lawyers would cost. Returns are clear enough that AmLaw 100 firms, notoriously cautious about technology - are adopting rapidly.

What makes this company significant for the broader vertical AI thesis is the speed - from founding to $100 million ARR to serving 50 of the top 100 law firms happened faster than comparable SaaS companies achieved similar milestones.

Legal services is one of the most conservative, relationship-driven, and change-resistant industries in business. If vertical AI can penetrate law at this velocity, the model will work even better in less conservative verticals.

To this date, Harvey raised approximately $760 million in 2025 alone from investors including Sequoia Capital, Kleiner Perkins, Andreessen Horowitz, and OpenAI's Startup Fund.

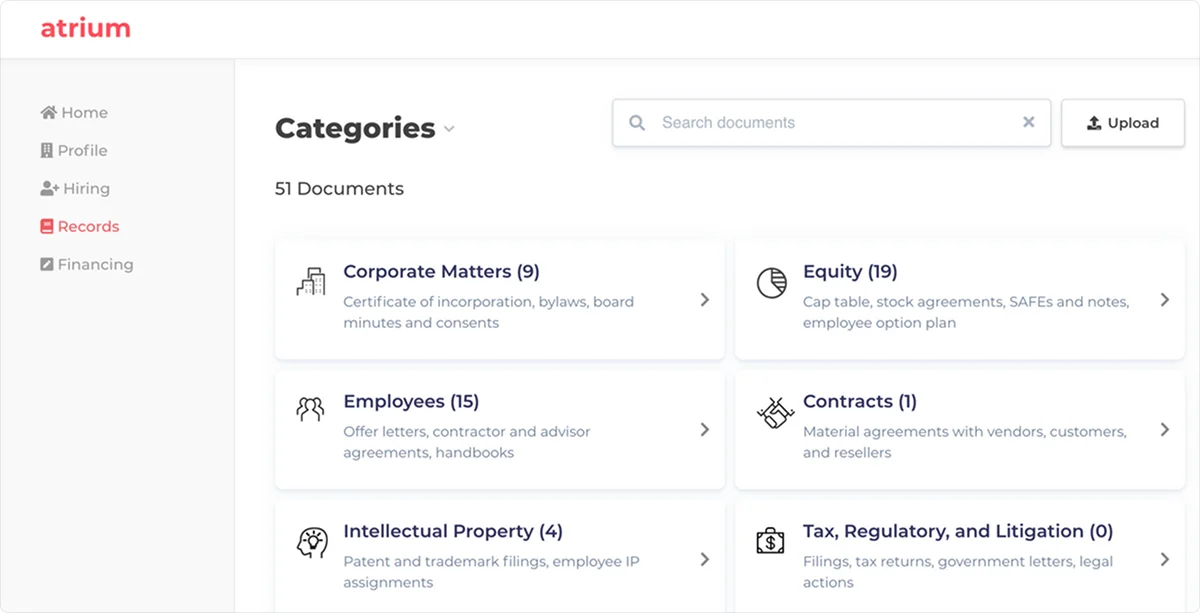

When the market wasn't ready (2017-2020)

The full-stack AI model isn't new as a concept. What's new is that the technology finally works well enough to make the economics viable.

The cautionary example is Atrium, the legal services company founded in 2017.

After selling Twitch to Amazon and establishing himself as a successful founder, Justin Kan saw the same opportunity current founders see: legal services are expensive, processes are manual, and technology should enable a better model.

Atrium launched as a hybrid - legal software plus law firm services, owning both the technology and the delivery.

The company raised over $75 million from top-tier venture investors who believed in both the founder and the thesis. Atrium hired lawyers, built software, and went to market with a model that looked remarkably similar to what Garfield and Harvey are executing today.

Own the technology, own the service delivery, compete on price and efficiency against traditional firms.

It failed. Atrium shut down in 2020, just three years after launch.

Kan's explanation was direct: the company couldn't operate more efficiently than a traditional law firm." The technology wasn't mature enough to actually replace legal work at the volume and quality required.

https://x.com/justinkan/status/1235358149541941248?s=20

This is the critical lesson about timing. Atrium had the right model, the right market, experienced founders, and substantial capital.

What it didn't have was technology capable of actually executing the model. 2017 AI couldn't do what 2024 AI can do. The tools for legal research, document generation, and case analysis existed, but required too much human oversight to change economics significantly.

On the other side, Harvey today uses frontier language models that can actually analyze case law, draft legal documents, and handle research at scales that weren't possible in 2017.

Garfield's AI can process debt collection workflows end-to-end with minimal human intervention. The technology matured enough in the seven years between Atrium's launch and the current wave that what was impossible became routine.

Where value lives

Technology inventions follows patterns that create market cycles, and it has been like this for decades. What was scarce becomes abundant, and value migrates to the next layer that remains scarce.

- Computing power commoditized in the 1980s, shifting value to software.

- Software development commoditized with cloud and SaaS, shifting value to implementation and distribution.

- AI is commoditizing execution itself, shifting value to whoever owns the complete outcome.

Building software became cheap, while the implementation became expensive - this inverted two decades of conventional wisdom that software always beat services because tools scale without adding headcount.

Y Combinator, world’s most successful startup accelerator is usually leading the changes in technological industries, so their bet on FSAC model suggests it’s not incremental - it's closer to fundamental reorientation of industry in general toward companies that own both technology and delivery rather than selling tools to incumbents.

The pattern won't apply universally.

Horizontal tools still win when implementation is straightforward, and customers can extract value without extensive support. But in verticals with high labor costs, manual processes, regulatory complexity, and persistent implementation gaps, the full-stack model captures value that tools cannot.

The next decade will feature vertical AI agencies competing directly with traditional incumbents - not by selling software to these industries, but by becoming AI-powered versions of these industries. The moat isn't the technology anymore. It's owning implementation at scale.

All of the data suggests that where the value lives has changed, and moved from building to implementing, from selling avg. efficiency per employee increase to delivering outcomes, from horizontal tools to vertical agencies.

The companies succeeding in this transition aren't those with the best AI models - they're those who combine AI capabilities with domain expertise, regulatory navigation, and the willingness to own the entire value chain from technology to service delivery. That's where the next generation of billion-dollar companies is being built.

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.webp)

.png)

.png)