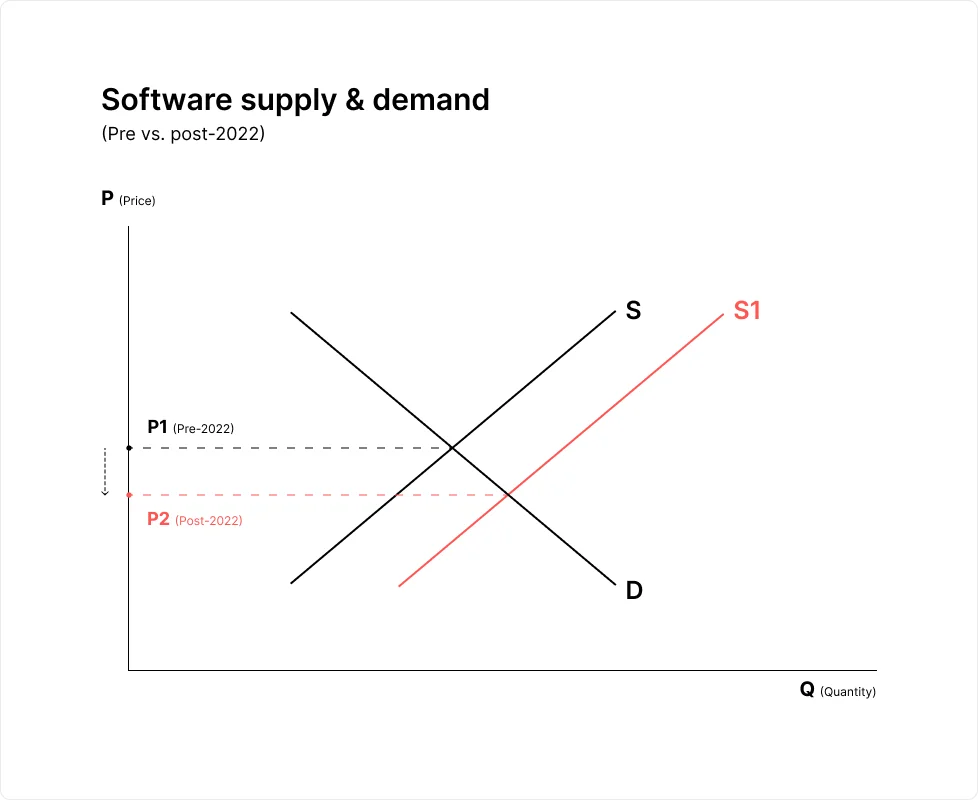

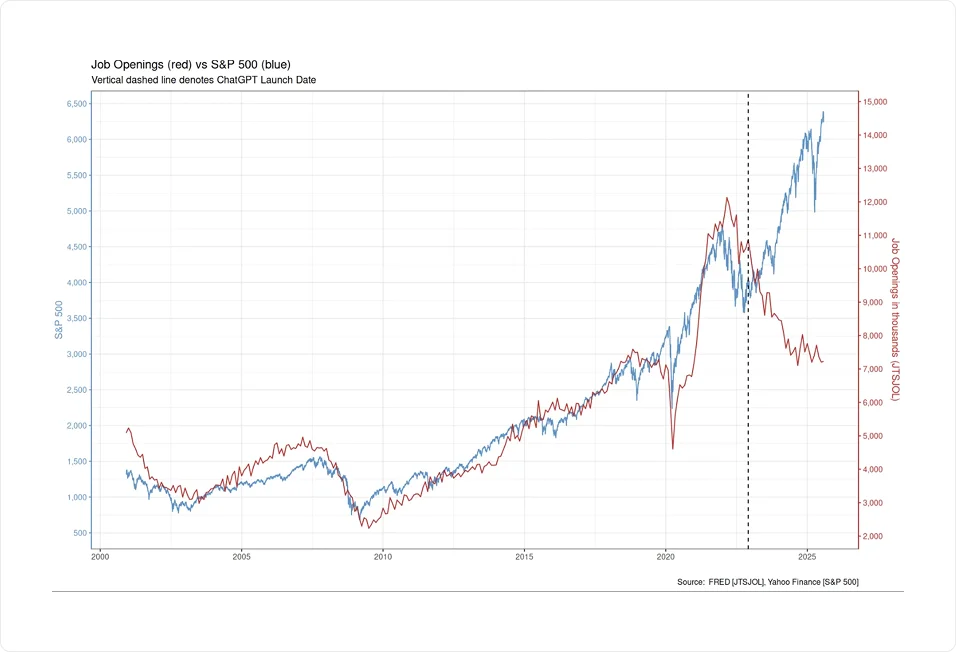

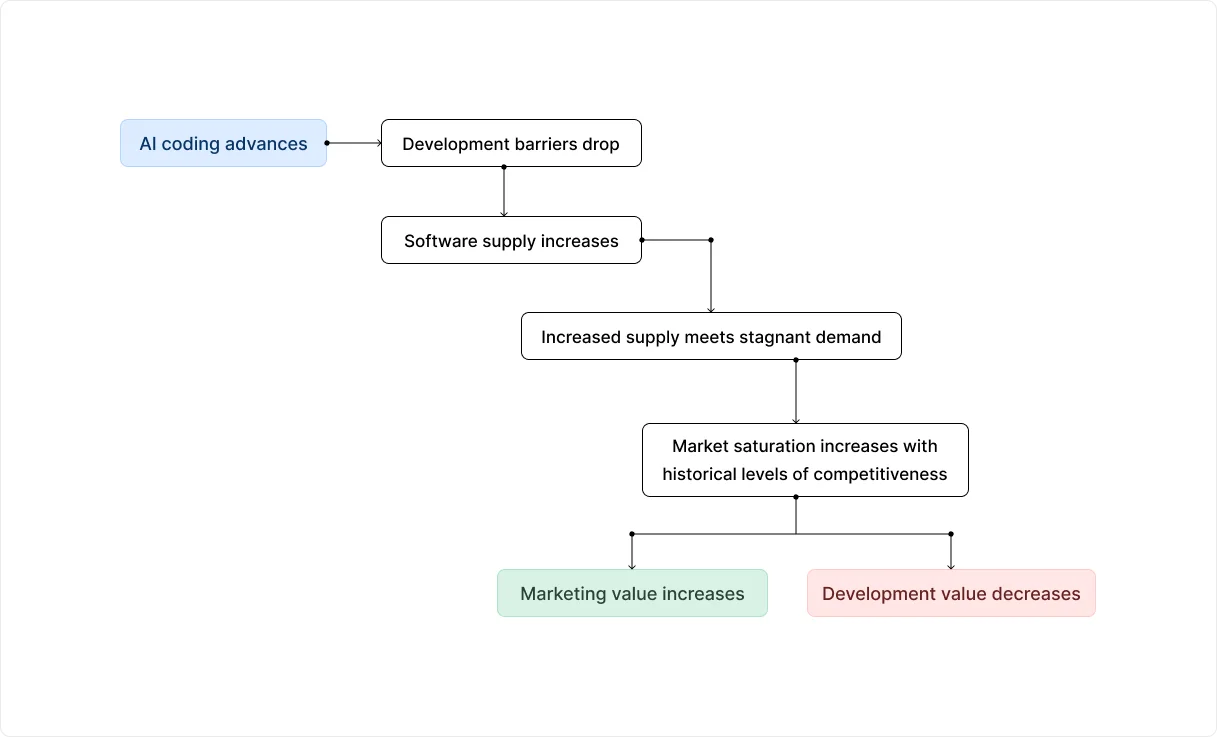

Post-2022, we can see the negatively-correlated influence of AI technology on development and marketing. Software development is being “shorted”, while software marketing is becoming the new biggest problem (financially) worth solving.

Moat has moved.

AI is commoditizing development

(The probabilistic/deterministic part of it)

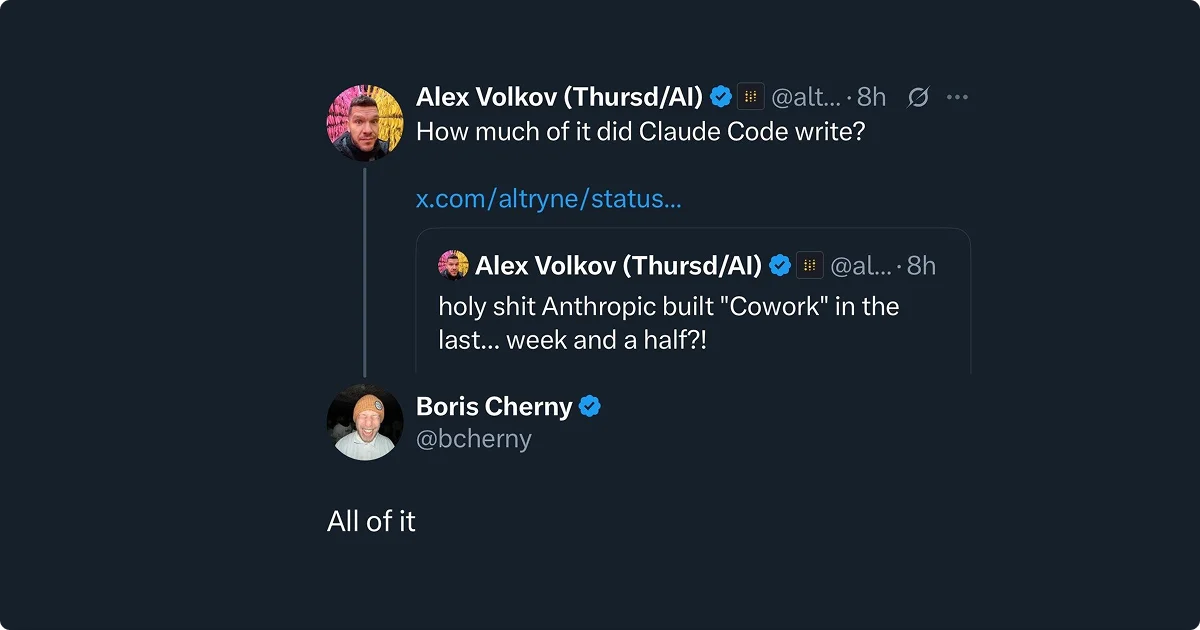

A simple test of whether development is becoming a commodity is whether output is decoupling from headcount. That decoupling is now being stated plainly by the people closest to the work.

In January 2026, Google principal engineer Jaana Dogan wrote that Google teams had been building “distributed agent orchestrators” over the prior year, with multiple options and not everyone aligned, and that after describing what she wanted, Claude Code generated “what we built last year” in about an hour.

Y Combinator is reporting the same thing in aggregate.

YC managing partner Jared Friedman said that about 25% of the Winter 2025 batch had startups where 95% of the codebase was generated by AI.

Anthropic’s own behavior provides an even cleaner proof. Their agent product Cowork was reported as being built largely using Claude Code in under two weeks. And the company placed it behind Claude Max, priced at $100 or $200 per month.

And these abilities aren’t reserved only for Big Tech.

Midjourney founder Dave Holtz said he did more personal coding projects over one Christmas break than in the prior ten years.

A single developer, Maor Shlomo, built Base44. The product reached $1M ARR in three weeks, grew to 400,000+ users, and was acquired by Wix for $80M+ - all within roughly six months.

What these examples show is not (only) “better developer productivity.”

It is that development is starting to behave like a commodity. Becoming:

A) Broadly available

B) At low cost now,

C) With negative hiring trends.

The same that happened to computing in 2006.

Back then, AWS didn’t “make system administrators more productive” - but made compute capacity mass-available, and then kept compressing the price. As a result, entire categories of work moved from headcount-heavy infrastructure teams to on-demand consumption.

AI is now applying the same logic to development.

What makes development commoditizable is that a large portion of it is probabilistic (repeatable pattern work where the same inputs lead to the same outputs). Once you’ve built authentication, billing, permissions, dashboards, webhooks, or CRUD flows, you’re reassembling the same blocks with lower marginal effort for every new iteration.

Ironically, developers spent decades modularizing software into reusable blocks, through frameworks, libraries, APIs. AI has learned, and now implements it on scale at a fraction of the cost, thus commoditizing the work of development itself.

Near-infinite supply meets not-infinite demand

Software supply has been growing asymmetrically, due to lowered entry barriers.

Let’s take a look at the data.

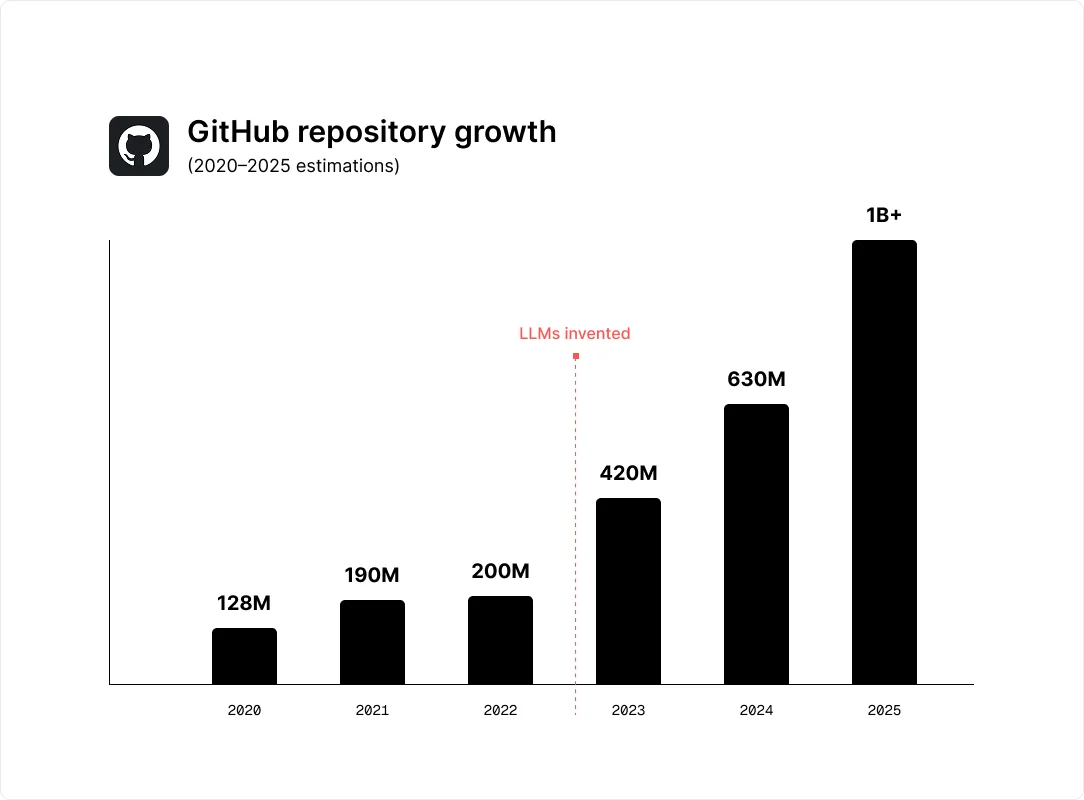

On the production side: GitHub repositories grew from 200 million in 2022 to 1 billion in June 2025, which is a 5x increase in under three years. In 2025 alone, the platform added 121 million repositories, approximately 230 created every minute.

On the deployment side: Vercel grew from $86M ARR in 2023, to $144M ARR in 2024 & beyond $200M by mid-2025. Doubling revenue roughly every 12 months in the post-2022 period.

So, it's fair to say that development (now commoditized to AI) has increased software supply in 2024/2025 period more than we could speculate. Well, most of us - Altman's 2023 hypothesis that we'll see billion-dollar one-person companies in the future now sounds more likely.

On the other hand, logically, we have a non-infinite demand.

The number of potential software buyers stayed ± stagnant.

Enterprise software spending grew 9.3% year-over-year in 2024 (±0% if we calculate in the inflation), reaching $8,700 per employee - but the average company reduced its software portfolio from 112 apps in 2023 to 106 in 2024/2025, consolidating vendors instead of adding net-new tools.

More critically, internal AI building capability is beginning to replace a portion of external software purchases entirely, as exemplified by Vercel’s CEO, Guillermo Rauch, who describes using a custom GPT-style agent to replace functions of an existing third-party app.

Customer acquisition costs (CAC) jumped on the order of 50-60% over the last five years, with recent benchmarks showing the median SaaS company now:

- Spends about $2.00 in sales and marketing to acquire $1.00 of new ARR, versus roughly $1.20-$1.40 in the early 2020s,

- With CAC payback periods, which historically clustered around 12-18 months, have stretched into the 20-24 month range by 2024/2025 in many mid‑market SaaS businesses.

This indicates that software pricing has not kept pace with CAC and inflation increases and that competition is intensifying far faster than the perceived value of software is growing.

When acquisition becomes this expensive and real software spendings are stagnant (to possibly down) in net terms, only one variable has really changed: there are far too many sellers competing for a structurally limited pool of software buyers.

All of the factors below:

- High software supply increase due to commoditized development,

- Stagnant to slightly net‑negative real software demand,

- Rising CAC and intensifying competition,

- Pricing (and perceived value) not keeping up.

Indicate that the software market is becoming highly saturated, where the main question (financially) worth answering is no longer “How to develop?” but “How to distribute?”, with significant consequences for the market.

Development value decreases

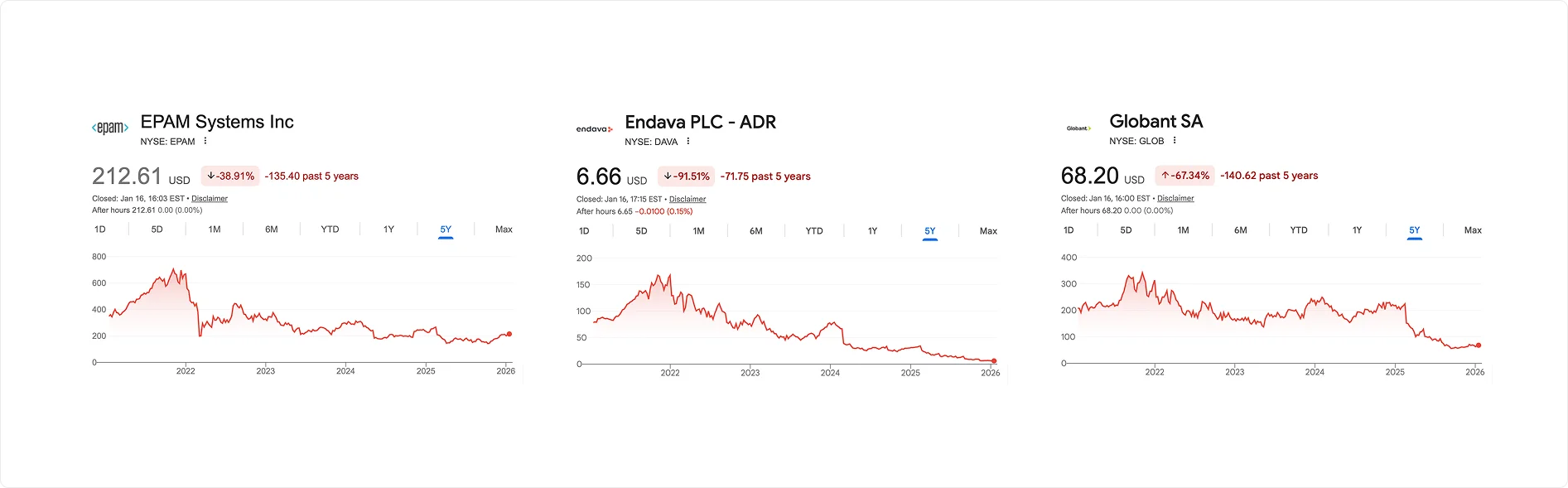

That supply/demand imbalance is now compressing development's market value. The repricing is visible in both public equities and compensation data.

The clearest proof comes from publicly traded software services companies that grew steadily for decades before hitting an inflection point in 2021-2022 (ChatGPT was launched on November 30, 2022, other LLMs followed shortly).

EPAM Systems reached an all-time high of $725.40 on November 5, 2021.

As of January 2026, it trades around $217 - a 70% decline. The company had grown revenue consistently at 25-30% annually through 2021 before growth decelerated sharply.

Endava peaked at $170.13 on December 27, 2021.

As of January 2026, it trades at $6.90 - a 96% collapse from its high. Like EPAM, Endava delivered stable double-digit growth for years before the decline.

Globant reached its all-time high of $354.62 on November 9, 2021.

As of December 31, 2025, it closed at $65.37 - an 82% drop despite maintaining revenue growth.

Accenture, the largest and most diversified, peaked at $389.49 on February 5, 2025. As of January 14, 2026, it trades near $288.54 - a 26% decline for a company of that scale and stability.

These are not startups that over-hired during a funding bubble, but established, profitable services businesses that grew predictably for decades, then saw their market value compress precisely when AI development tools began scaling.

And nope - this isn't just 2022's broad tech correction. The S&P 500 recovered to new highs by 2024, but EPAM, Endava, and Globant remain 70-96% below their peaks. The market is specifically repricing development work.

The same pattern appears in employment data.

Software developer job postings on Indeed fell more than 33% from 2020 levels to early 2025, reaching a five-year low. Software development job listings more than doubled in 2021-2022, then fell faster than banking, finance, or any other sector.

Layoffs in tech companies totaled approximately 200,000 in 2023, followed by another 95,000+ in 2024, with development roles disproportionately affected.

The U.S. was employing fewer developers in 2024 than it had in 2018, even as coding bootcamps continued to graduate thousands of new programmers monthly. For the first time in two decades, developer salaries were falling, down 9% to 15% depending on which market you looked at. Cloud architects saw compensation drop 15.8%, while front-end developers in major Australian tech hubs experienced declines from $180,000 to $165,000. Top engineers from FAANG companies were accepting offers up to 30% lower than their previous roles or struggling to secure positions entirely.

And this decline is happenning before full AGI-level coding agents. Anthropic's Coworker represents an early example of what becomes possible when agents handle complete work that currently require developers at $150K-$200K+ salaries, at a cost of $0.06-$0.10 per task.

The fact that AI can automate the probabilistic part of software development through agents at a fraction of the cost, combined with pessimistic-sentiment investors and job-pessimistic development agencies, points to a clear conclusion: Development is heavily decreasing in value due to AI.

Marketing value increases

Unlike development, market data suggests AI is increasing marketing's value.

The state of the market in 2025, where for every software category, there are now 5x more products competing (1 billion GitHub repositories in 2025 vs. 200 million in 2022) for the same number of companies that pay.

It’s logical to conclude that:

> Competition levels in the software industry are at historic heights

> Software marketing is becoming more important than ever.

Marc Andreesen’s thoughts align with this well:

"Distribution will soon be the only moat that matters."

Why hasn’t marketing been commoditized, as well?

In its nature, marketing is non-deterministic: the same input produces different outputs based on context. It exists in self-regulating environments where efficiency depends on what everyone else is doing.

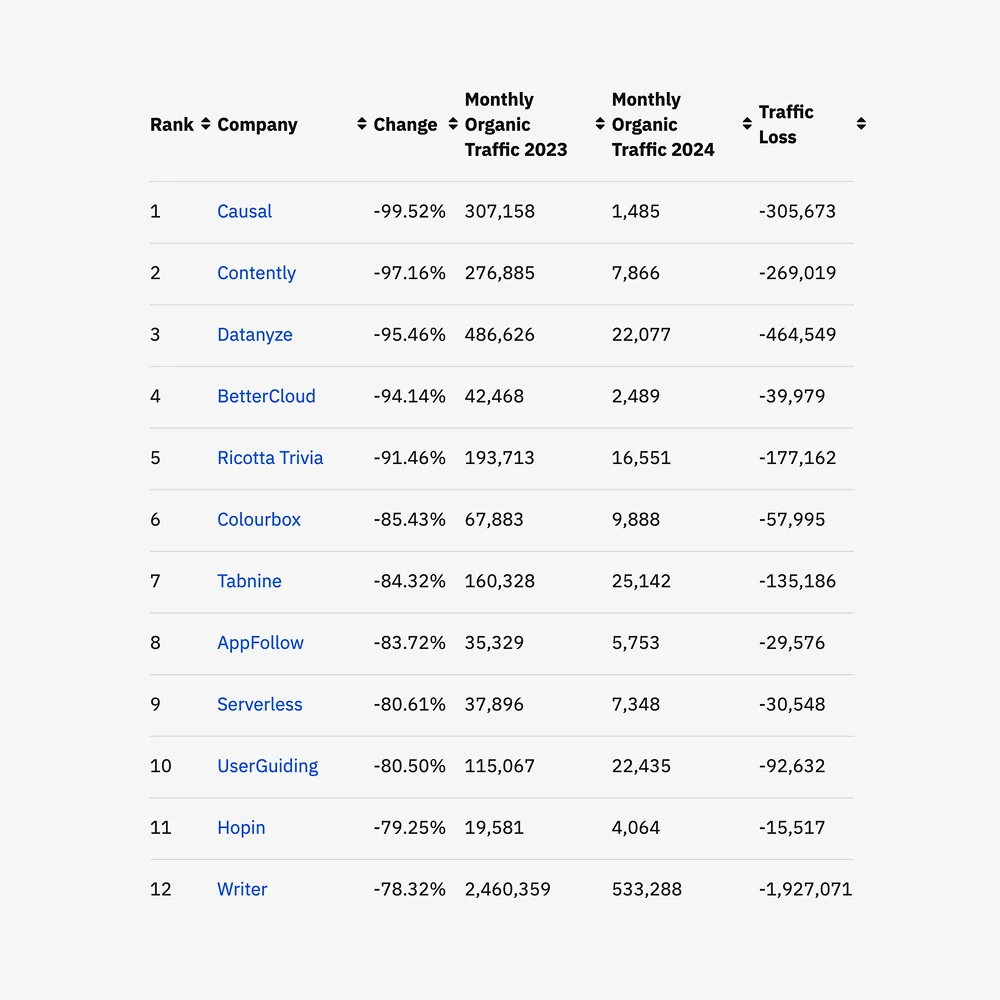

Consider our industry - Search Engine Optimization. AI text generation (probably the one automation you think of when thinking of potential AI commoditization of marketing) arrived in 2022. Jasper reached a $1.5B valuation.

> Content farms mass-produced articles

> Readers learned to recognize AI-generated content & opted out

> Google updated its algorithms.

By 2024, sites relying primarily on AI content lost 75-80% of organic traffic.

Jasper's revenue fell 53% from 2023 to 2025.

Short-term, AI made marketing more efficient. Long-term, we get to understand it was a false positive with a small short-term pump, and a big long-term dump.

The pattern repeats across channels. AI analyzes what worked historically and suggests the same strategy to everyone: Position around "AI-powered," "seamless integration," and "bank-level security," with a Linear-style purple-buttoned website.

Costs spike, conversion rates collapse, and, unlike in development, the pattern that worked becomes the pattern that fails precisely because everyone executed it simultaneously.

Marketing has answers that work until everyone else does them.

Then you need new answers.

Differentiation requires doing something the model wouldn't suggest - something that goes against conventional thinking or seems risky before there's data proving it works.

The companies that succeed in this environment make positioning decisions AI can't generate: contrarian bets that look wrong initially, strategies that defy conventional wisdom, and conclusions that emerge from deep customer understanding rather than pattern matching.

These marketing decisions remain valuable precisely because they can't be automated. For example, OpenAI made probably the most counterintuitive positioning decision in AI history.

When they released ChatGPT in November 2022, the consensus said conversational AI should be specialized - customer service bots, coding assistants, writing tools, each focused on a specific vertical.

Every AI company before them had picked a niche. OpenAI positioned ChatGPT as a general-purpose intelligence, deliberately avoiding specialization.

The product did everything adequately, instead of one thing perfectly. Industry observers predicted this would fail; users want specialized tools, not generalist ones.

But OpenAI saw what the data missed: people didn't want another chatbot, they wanted a thinking partner. By late 2024, ChatGPT had over 200 million weekly active users and generated $3.7 billion in annualized revenue. The positioning worked because it contradicted every AI product playbook written before it.

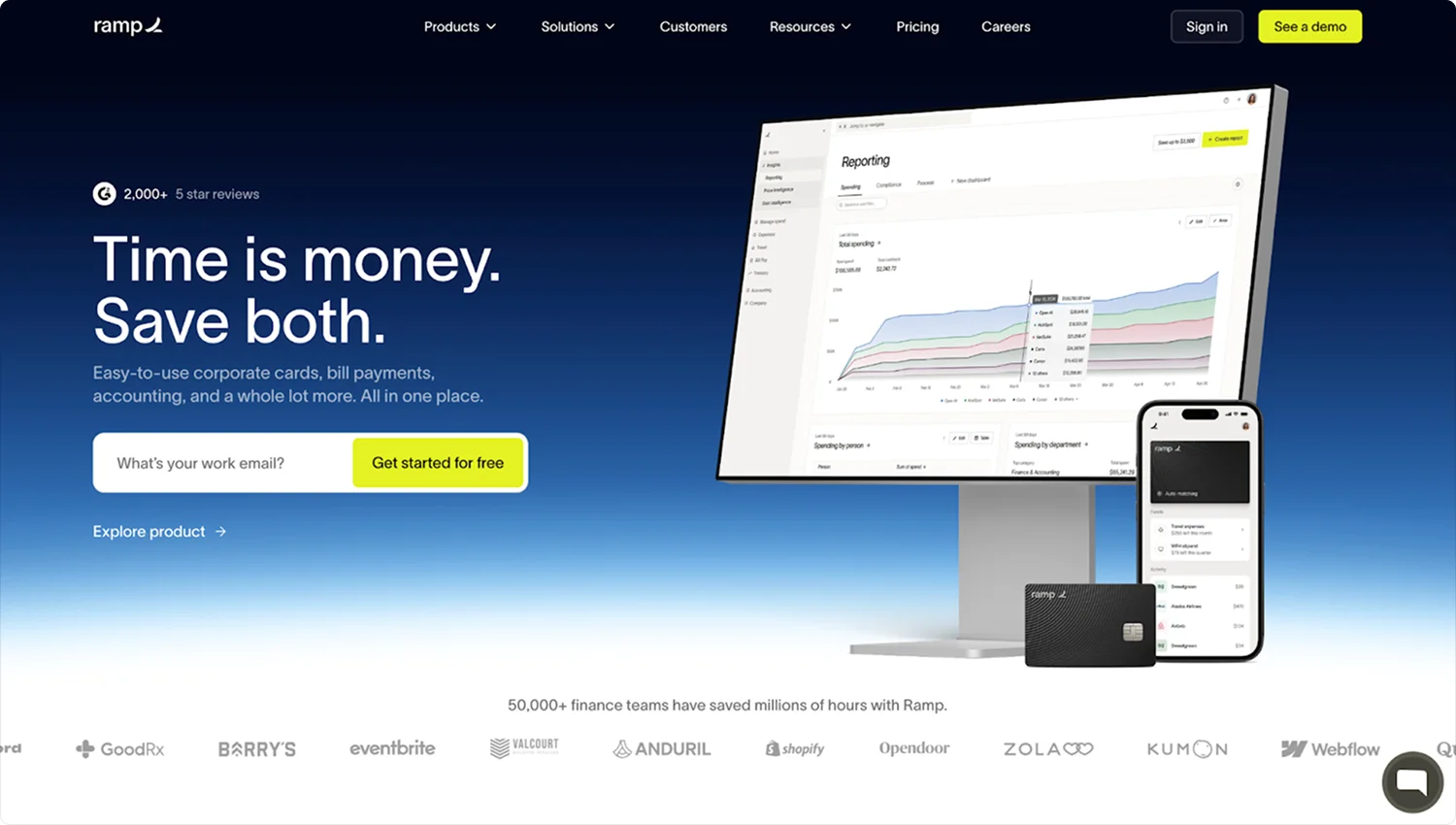

Ramp launched in 2019 into a saturated corporate card market and made a positioning decision that defied fintech logic.

Every competitor, American Express, Brex, Divvy, positioned on rewards points and credit limits.

They gave away corporate cards for free and charged for expense management software instead. The business model inverted what every fintech investor believed: credit cards make money on interchange fees, software requires ongoing development costs.

What Ramp understood, and others did not, was that CFOs didn't want another rewards program - they wanted spending control. The company reached an $8.1 billion valuation in 2022, increased to $32 billion by 2025 with over 50,000 customers.

They saved customers an average of 5% of expenses through automated policy enforcement that competitors positioned as features, not the core value proposition. The positioning succeeded precisely because it solved the problem customers actually had, not the problem market analysis said they should have.

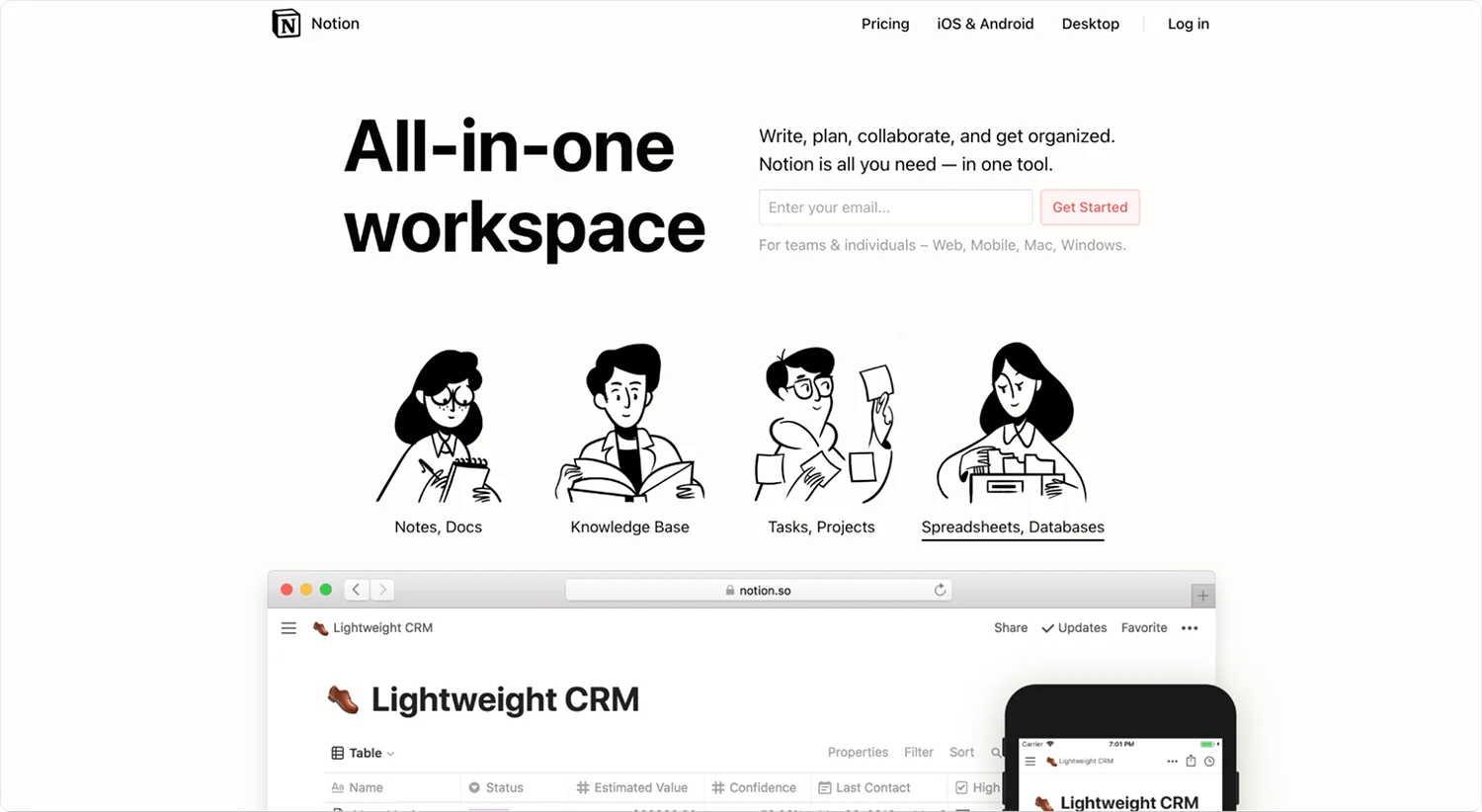

Notion made a positioning bet in 2018 that went against productivity software logic.

Every competitor, Evernote, OneNote, Google Docs - positioned as specialized tools solving specific problems: note-taking, document editing, project management.

Notion positioned as "LEGO blocks" for company workspaces - modular pieces that users combined however they wanted. The business model inverted conventional thinking: productivity tools monetize feature limits and storage caps. Notion gave away unlimited blocks for free and monetized team collaboration instead.

The positioning succeeded because it solved the problem users actually had - being stretched between dozens of specialized apps.

From 1 million users in 2019, Notion reached 100 million by 2024 with $500 million in annual revenue. The ratio of individual to company customers shifted from 90:10 to 50:50 in three years as enterprises adopted.

They captured over 50% of Fortune 500 companies not by building better note-taking or better project management, but by building a platform that replaced ten tools with one flexible workspace. The positioning worked precisely because it contradicted how every incumbent thought productivity software should be built.

All of these decisions share a pattern: each contradicted conventional wisdom of the time it launched, backed by years of market data. Each required conviction when the evidence argued against them, and each created differentiation that AI couldn't generate by analyzing what worked before.

Marketing defies commoditization just because of that.

Simply, context can’t be automated.

Data support the marketing upvaluing theory

Marketing budgets traditionally disappeared first when companies cut costs. CFOs protected engineering and slashed marketing, the standard recession manual repeated for decades.

The 2023-2024 tech layoffs broke the pattern.

Software engineers absorbed 22.1% of layoffs, while marketing took 7.1%. For the first time in tech history, marketing became more protected than engineering.

By 2024, 45% of CFOs planned to increase marketing spending while cutting development costs, with marketing budgets increasing from 6.4% of company revenue to 9.1%.

Salaries confirmed the inversion. Marketing managers earned $161,030 in 2024 - $28,000 more than software developers at $133,080. Marketing employment grew 12% as developer employment fell 33%.

Public markets are a good proxy for the analysis. While development agencies collapsed, Publicis, one of the biggest marketing agencies, grew from €7 billion (2019) to €21.4 billion (2025). Company’s CEO raised revenue forecasts three times during 2023. Stock increased 41% that year alone.

The conclusion writes itself: as AI commoditizes development, it accidentally created the new holy grail of the software industry: marketing. When every software company can build a competent product in weeks instead of months, the competitive advantage transitions entirely to the question AI can't answer: How to monetize it?

The companies spending millions on engineers to differentiate through the infinite number of "this is the one" features are implementing pre-2022 thinking. The ones prioritizing investing in marketing to differentiate through positioning, distribution, and customer understanding are building the only moat that matters in a world where code is (coming close to) free.

Moat has moved

AI split knowledge work into two negatively correlated categories (which looks like one of the characteristics of this technology, in general).

Probabilistic work that’s being commoditized.

Non-deterministic work that appreciates.

Development exemplifies the first, with relevant market indicators (salaries, jobs, budgets, valuations) going down from 2022 to 2025. Marketing exemplifies the second, with the same indicators going up.

For the good part of the last two decades, parents' career advice for their kids was "learn to code," with universities expanding computer science programs and bootcamps proliferating. But based on this value inversion (that will expand in years to come), it wouldn't be a stretch of imagination to say that in the post-2022 decade, this advice will likely change to "learn to market."

Lastly,

“If you’ve invented something new but you haven’t invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business - no matter how good the product. Superior sales and distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation. The converse is not true.”

Peter Thiel made this prediction in 2014, within his Zero to One book.

The market is proving it a decade later.

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.png)

.png)